Deriving the scalar product for vectors formula with the cosine rule and Euclidean geometry

The scalar (or dot) product of two vectors is used for finding angles between where two direction vectors would intersect, and that’s pretty cool. What’s more is that this works in more than 2 dimensions, such as 3D spaces and probably has all sorts of real world applications as vectors usually do.

It is also well known that it is defined as \(\mathbf{a}\cdot\mathbf{b}=|\mathbf{a}||\mathbf{b}|\cos\theta\).

However, what I felt unhappy about is the way that my maths textbook set about ‘proving’ it. It made the logical deduction that two vectors are perpendicular iff (if and only if) the scalar product is zero (since \(\cos\left(90^\text{o}\right)=0\)). But then, it decided muliply two arbitrary vectors together (using i, j, k forms) as though the vectors were just ordinary brackets!

This didn’t feel right to me so I set about devising my own proof.

So while the following may not be too pretty or rigourous, it gives me a much more fulfilled feeling of understanding and conviction than the textbook version has. Et voilà:

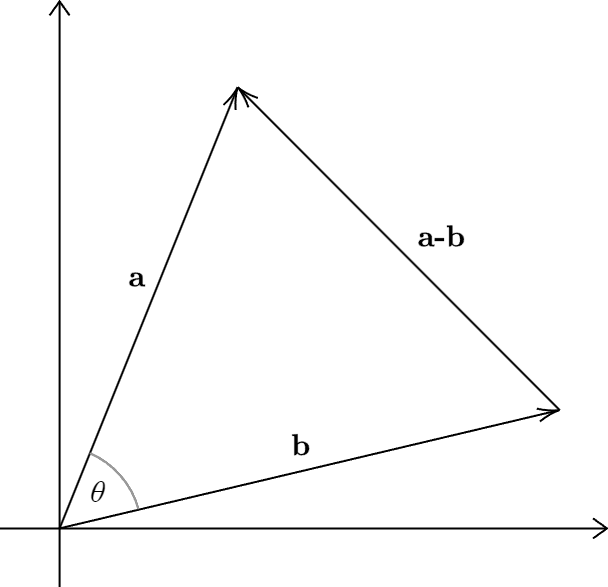

Suppose we begin with \(n\)-dimensional vectors \(\bf{a}\) and \(\bf{b}\) such that we form a triangle in the plane using vector \(\bf{a}-\bf{b}\), treating all of these as position vectors for now.

Hence, \begin{align} |\mathbf{a}| &= \sqrt{a_1^2 + a_2^2 + \cdots + a_n^2}\notag \end{align} with a similar result following for \(\mathbf{b}\). But, for \(|\mathbf{a}-\mathbf{b}|\), we should expand the brackets within the modulus to give \begin{align} |\mathbf{a}-\mathbf{b}| &= \sqrt{(a_1^2 -2a_1b_1 + b_1^2) + \cdots + (a_n^2 - 2a_nb_n + b_n^2)}\notag \end{align}

From the diagram above, it becomes clear that \begin{align} \cos\theta &= \frac{|\mathbf{a}|^2+|\mathbf{b}|^2-|\mathbf{a}-\mathbf{b}|^2}{2|\mathbf{a}||\mathbf{b}|}\notag \end{align}

\begin{align} \notag\cos\theta &= \frac{\left(\sqrt{a_1^2 + a_2^2 + \cdots + a_n^2}\right)^2+\left(\sqrt{b_1^2 + b_2^2 + \cdots + b_n^2}\right)^2-\left(\sqrt{(a_1^2 -2a_1b_1 + b_1^2) + \cdots + (a_n^2 - 2a_nb_n + b_n^2)}\right)^2}{2|\mathbf{a}||\mathbf{b}|} \end{align}

\begin{align} \cos\theta &= \frac{2\left(a_1b_1+a_2b_2+\cdots+a_nb_n\right)}{2|\mathbf{a}||\mathbf{b}|}\notag \end{align}

\begin{align} \implies |\mathbf{a}||\mathbf{b}|\cos\theta &= a_1b_1+a_2b_2+\cdots+a_nb_n\notag \end{align}

From the original definition, we also know that \begin{align} |\mathbf{a}||\mathbf{b}|\cos\theta &= \mathbf{a}\cdot\mathbf{b}\notag \end{align}

and equating the two RHSs of these equations, we get \begin{align} \mathbf{a}\cdot\mathbf{b} = a_1b_1+a_2b_2+\cdots+a_nb_n \notag. \end{align} for the vectors \(\bf{a}\) and \(\bf{b}\), which I’d probably call the end of this ‘proof’.

This is recognisable to most of us as the ‘quick’ form of the scalar product, and it has given me a huge feeling of relief to have shown it using a method I fully trust (the law of cosines) as opposed to just blindly having faith in some cockamamie ‘proof’ from some textbook. Maybe it’s instilled similar feelings in you, the reader, as well.

Also, please let me know if I’ve done something totally wrong or have anything to add, either by email or on any of the other linked socials, or maybe even the comments section if that’s working.

Comments